My goal with this post is to try to explain to someone who’s really into philosophy (i.e. my past self) why philosophy can sometimes be a waste of time.

Doing philosophy helps you get better at constructing and deconstructing arguments; surprisingly, this does not always make you better at figuring out the truth.

If you’re really good at constructing arguments, you will be better at convincing yourself of any particular belief you’d like to have, regardless of whether it’s accurate. You get better at answering the question: “what are the ways in which this might be true?” and “what are the ways in which this might be false?” rather than the question “is this true or false?”

Constructing and deconstructing arguments is one part of being in touch with the truth, but the other, equally crucial part is being able to deploy attention and emotion skillfully. Being attuned to your emotions helps you better understand your motivations around a particular belief, which is crucial for assessing its accuracy. Traditional philosophy doesn’t help you with this because it doesn’t encourage you to introspect.1

When I originally discovered philosophy, what I found particularly appealing about it is that it seemed like the king of intellectual pursuits, because it was asking the deepest questions. What is the fundamental nature of reality? Where does ethics come from, does it exist in any objective sense? But just because you are asking the questions—and constructing and deconstructing arguments about them—does not mean you are getting closer to answering them. For both of the above questions, we have spent thousands of years arguing about them, and haven’t made much progress.2

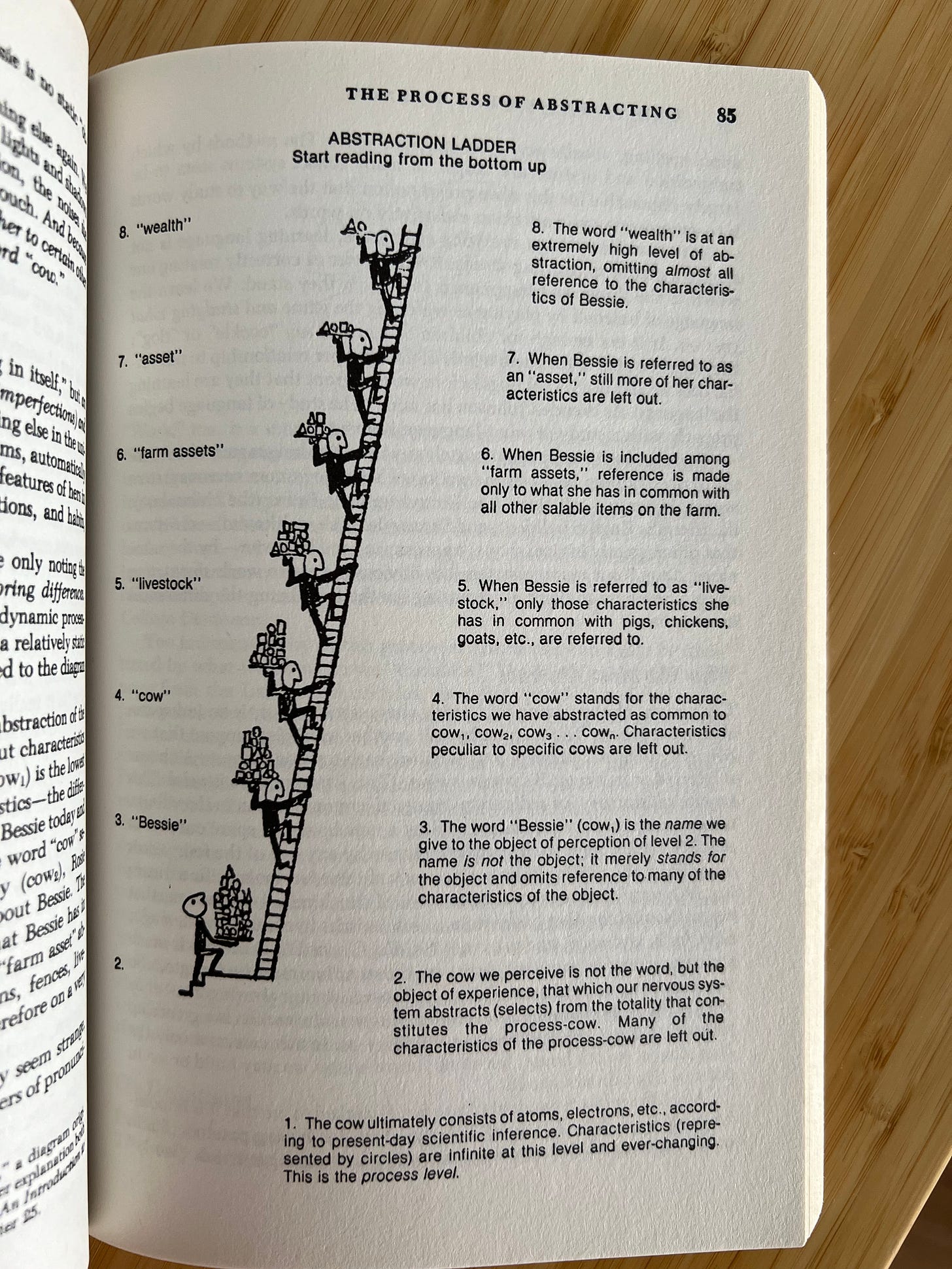

These days I think the “ladder of abstraction” is very important when thinking about philosophical discussions:

The idea is that the things at the bottom of the ladder are very “concrete”, i.e. they are things you can fairly easily point to (like the chair you’re sitting on), whereas the things at the top of the ladder are much more “abstract”, they are much broader (e.g. “wealth” or “justice”). I believe this concept originally came from S.I. Hayakawa’s Language in Thought and Action:

The point of the ladder is that there are basic facts that are very easy for us to agree upon, and then there are facts that are higher up that are very hard for us to agree upon. The lower levels of the ladder give you a bunch of “consensus for free.” No matter your political beliefs or philosophical inclinations, you will agree that in front of you is a cow. No matter your worldview, you will agree about whether it’s daytime or nighttime.3

Here are two conversations about the color red, one of which moves down the ladder of abstraction and the other moves up (taken from this article):

Case 1: Moving up the ladder of abstraction (less helpful):

“What is meant by the word red?”

“It’s a color.”

“What’s a color?”

“Why, it’s a quality things have.”

“What’s a quality?”

Case 2: Moving down the ladder of abstraction (more helpful):

“What is meant by the word red?”

“Well, the next time you see some cars stopped at an intersection, look at the traffic light facing them. Also, you might go to the fire department and see how their trucks are painted.”

The higher up the ladder you go, the looser your grip on reality gets. Philosophy exists purely at that highest level of abstraction. Rather than speaking of, for example, how much water your plants need to be fed to stay alive, you talk about whether, for example, propositional knowledge captures everything there is to say about reality, or whether it’s possible that abstract patterns in non-sentient matter could generate conscious experiences. It’s very high up the ladder. Far away from action, far away from specificity, far away from things you can see and touch and taste. This doesn’t mean that it is totally devoid of substance: just that it is harder than in any other field to know whether you’re studying something of substance or not.

Here’s a specific way that this played out in my own life. I spent a lot of time being obsessed with the ideas of Karl Popper and David Deutsch. I was totally enamored by the universality of explanations, by conjecture and criticism as the fundamental process driving science and society, by a theory of knowledge and of biology centered on error-correction. Now I look at all these ideas and I think: meh, there isn’t that much there, they are not that deep because they don’t map to the real world as much as I thought they did.4 But a few years ago I was spending many dozens of hours arguing, futilely, with friends about how these are really such deep and profound and important insights!! And I could never quite convince anyone who wasn’t already really into philosophy, and really into Deutsch and Popper specifically, why they mattered.

Because of the nature of philosophy, you have to be really good at introspecting in order to do it well. You have to have a deep understanding of your own thought processes and emotions. I don’t just mean more theories about your emotions; I mean actually knowing yourself, knowing the ways you tend to lie to yourself, knowing the things that trigger you, being able to experience those triggers without your awareness totally collapsing. Not knowing yourself, in the sense I’ve described, will do more damage to your ability to think clearly than any amount of philosophical inquiry can compensate for.

Does this mean philosophy is always a waste of time? No. First of all, there is a richness to exploring these questions, assuming they are the kind of question that tickles you. When engaged with skillfully, philosophy can make you more appreciative of the beauty and mystery of existence. Also, there are practical benefits to getting better at constructing and deconstructing arguments—you become a slightly better thinker, writer, scientist, et cetera. You become harder to fool by others, even though in some sense you become better at fooling yourself.

Beyond that, I think the benefits of philosophy are overstated. In particular, I think people who cling very strongly to the idea that you need to do philosophy to understand the world and live well are wrong. “Philosophical beliefs” are largely irrelevant to our existence in the world; they are irrelevant to almost everything we do, except for very specific edge cases, like being a quantum physicist or being a neuroscientist trying to understand consciousness. If you’re trying to do those things, having a strong background in philosophy seems very helpful, otherwise it largely isn’t.

Now. Even with all those caveats mentioned, I have to admit that philosophy is something that continues to draw me in, because I’ve always had a soft spot for the deepest questions. In a recent tweet thread about the nature of math, mathematician David Bessis said that “mathematics and philosophy are the only two human activities completely of the mind,”5 and, well, I’m a sucker for activities that are completely of the mind. I love it when I can find a small number of ideas that cover a lot of ground—they make me feel powerful, they give me some sense of control in a life that is otherwise full of overwhelming uncertainty. It’s just that, unlike a few years ago, I am much more honest with myself about these things—about the actual reasons I’m doing philosophy, and the actual impact it has on my life (which is often negligible). When I read philosophy now, I approach it less in the spirit of Finding The Ultimate Answer, and more in the spirit of “let’s read these fun little fairy tales and maybe they’ll give me a sense of clarity about something.”

My point about philosophy is that there is nothing necessary about it. Of course it’s good to look at the world with curiosity, and to think critically, but I think you can do all of that without philosophy. It’s very easy in philosophy to feel like you’re doing something important by talking and thinking a lot about deep questions — and so it will naturally draw people who enjoy thinking and talking, because it tells them that the thing you like to do most in the world is also cosmically significant. And in a very loose sense it is. But it is not uniquely so.

Thanks Sid for discussion and comments.

Appendix

A few other thoughts/nuances I couldn’t fit into this essay nicely:

In the process of writing this post I realized I’m talking about a rather specific kind of philosophy, which some might call the analytic tradition, and which I would describe as “trying to talk very rigorously about deep meta-questions that are outside the purview of ordinary sciences and humanities.” This doesn’t capture everything that could conceivably fall under the umbrella of “philosophy” (e.g. in my view existentialism and phenomenology don’t fall under it). But I do feel like this specific kind of philosophy is overrepresented among people who talk about it on the internet, and so it’s the definition I stuck with.

The astute reader would point out that the “ladder of abstraction” is itself an abstraction. And yes, it is. Anytime we use language we are employing abstractions. I don’t think this matters. The point is that there is such a thing as “more concrete” language and “less concrete” language and that it’s much easier to get lost in the sauce when you’re engaging in the latter.

Also, someone might point out that items on the lower level of abstraction are not actually easy for us to agree on; e.g. at what exact point is it no longer “daytime” and now “nighttime”? Different people can disagree about this, just as different people can disagree about whether a hot dog is a sandwich. In my view this results from the fact that any category we impose on the world is necessarily blurry at the edges.6 But there is still a crucial difference about the kinds of disagreements we might have at the lower vs higher levels of abstraction. At the lowest levels of abstraction it’s very obvious to the participants that the debate is merely a semantic one, i.e. it’s about arbitrary word definitions. What happens at the highest levels, though, is that it’s harder to tell whether your disagreement is merely about arbitrary definitions or whether it’s more substantive.

There’s a specific class of philosopher who, in response to this post, would say: “well, your argument about philosophy being a waste of time is actually a philosophical argument; thus it refutes itself.” I used to be convinced by this argument and I no longer am, but it’s hard to articulate exactly why. Roughly, it’s something like this: if you take this view (that you can only refute philosophy with more philosophy), then philosophy becomes literally inescapable. In this view of the world you are constantly doing philosophy whether you realize it or not; and in the extreme it also means that babies are doing philosophy and so are monkeys and wasps. Another tenet of this worldview is that “if you believe X, that means you necessarily believe all the imaginable logical implications of X.” I think this is based on a fundamental misunderstanding of the nature of human belief. So, I don’t find it convincing. You don’t have to refute philosophy by doing more philosophy; you can just refute it by putting it aside and living life.

This isn’t true of all philosophers or traditions in philosophy. For the purpose of this post I’m referring mostly to what people would call “analytic philosophy”, e.g. Kant, Hume, Popper, Wittgenstein. Popper is a particularly bad example here, because he actively advises against thinking about the psychology of philosophical debates because it’s a distraction from the “content” of the debate (see §2 of Logic of Scientific Discovery).

To be fair, I think we have made some progress on these questions compared to a thousand years ago, but to the extent that we’ve made progress on them it hasn’t really been through philosophy itself but more through science, history, etc. (And I realize that historically, science was an outgrowth of philosophy, but that further serves my point: the questions became easier to answer once they were no longer philosophical.)

Here is where a specific brand of philosopher (including my past self) would object. They would say: no, we don’t agree on basic facts, because observation is theory-laden. There are no pure, indisputable observation statements. I think this point is kinda true in a technical sense, but it misses something very important about the nature of our experience in the world. I plan to expand on this at some point in the future, but for the time being I invite you to ponder this quote by John Worrall: “if you go to a low enough level (to the level of what Poincare called ‘crude facts’ and Duhem ‘practical facts’ – meter readings, angles of inclination of telescopes, digital printouts and the like) then there is, I claim, no case in the whole history of science where a once accepted, well and independently checked, low level observational generalization turned out subsequently to be falsified.” From Freedom and Rationality: Essays in Honor of John Watkins.

Okay, so philosophy is super abstract and hence it’s hard to make progress in it; what about math? My thinking about this is still a bit hazy but here’s my answer. Because math progresses by way of proofs, there is a kind of intersubjective rigor to it that does not exist in philosophy. In math, you could still be talking about nothing (as in, your theorems could refer to things that don’t actually exist in the world); but because of the robust methods of criticism, you’re capable of “remaining on the ground” even while talking about super abstract things. In other words, you’re able to solve problems definitively (or close enough to it), so there’s less of a concern that you’re literally making no progress talking about nothing.

I thought Franklin & Graesser put this especially well when they said: “The only concepts that yield sharp edge categories are mathematical concepts, and they succeed only because they are content free.” Also I think David Chapman’s ideas about nebulosity & pattern are very helpful for thinking about the limitations of categories.

I don't think I was ever really into philosophy as you put it then. My version of philosophy has always included engaging with different ideas in unison with introspection and intuition as a path towards wisdom and meaning.

I have tried to get into some of those abstract theories but honestly they kinda put me off. I try to find what's useful and how it connects to other things rather than just building and breaking down arguments.

Been reading some Simone Weil recently and I love how her philosophy is a lived one. I definitely think there is danger in the allure of too much abstraction, as you and she mentioned.

Very interesting piece, I appreciate the different perspective :)

I can really relate to this, I've been writing about a very similar feeling towards philosophy in my last couple of posts