I love words but I don't trust them

a collection of rough notes on my relationship to language

tl;dr

language can deceive us in a number of ways: by confusing our concepts for the things they point to; by making things appear more insightful than they really are; by trapping us in logically unassailable webs of belief; among others.

people who have noticed the pitfalls of language and/or glimpsed the freedom of silencing the inner monologue can develop a sense that language is the enemy. but this is mistaken, because language is necessary for our continued existence, and arguably fundamental to our humanity.

we can use language itself (and various attentional practices) to escape the traps of language. we can reclaim some of the “purity” of pre-language consciousness, without disowning thought altogether. admittedly, striking this balance is extremely difficult.

I know I’m not the only person who thinks about their relationship to words because I see tweets like:

and also:

Let’s break this down.

words are fake

In her memoir on writing, Anne Lamott says:

Ever since I was a little kid, I’ve thought that there was something noble and mysterious about writing, about the people who could do it well, who could create a world as if they were little gods or sorcerers. All my life I’ve felt that there was something magical about people who could get into other people’s minds and skin, who could take people like me out of ourselves and then take us back to ourselves. And you know what? I still do.

The word ‘magical’ is an interesting choice because ‘magic’ can have two connotations: there’s magic as in weee this is so nice and magical wow and there’s also magic as in booo this is fake, this is a conjuring trick.

I agree with Lamott that words have a magical power to take us out of ourselves and back into ourselves. But also, words are fake, in a few ways.

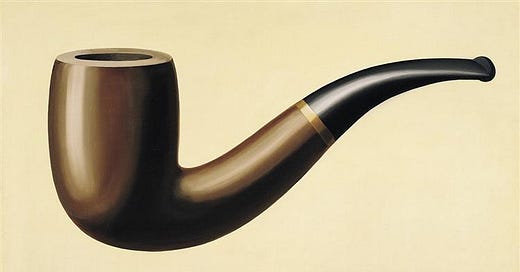

fakeness #1: map vs territory

As Vivid Void pointed out in his tweet above, language can form this “dense thicket” that gets in the way of our experience of the world. Often we conflate our idea of something for the thing itself. The map can block our view of the territory, or even make us forget that there is a territory distinct from the map. A word is an inert, static map—a dead referrer—whereas the referent is alive, changing, and ephemeral. My friend Christophe Porot once said:

Words are old but the experiences we have are new. When we look at a rose, with all its delicate and vibrant petals, we classify it as this common thing through the word we impose upon it. But in reality, every time you look at a rose, it’s a sensational experience demanding a whole new word to describe how it makes you feel. As I passed by a tree blossoming with pink flowers, it was a pleasure to have a wordless response to it. I perceived it directly, without it being dressed up by an indexing system which generates the perception that it is known. It was fresh, new life budding for the first time as my eyes fell upon it for the first time—I was rightly confused and mesmerized.

fakeness #2: unwarranted shimmer / false insight

The preceding quote is an example of a word hiding the shimmer of reality by making us think we’re familiar with something we’ve never actually seen before. But words can also add a “fake” shimmer to something that’s not actually shimmery. Cedric Chin writes about how something can sound insightful and interesting while being wrong (emphasis mine):

David Perell has a famous essay titled Peter Thiel’s Religion. The essay is the length of a small booklet, and is divided into tiny sections, each ending with a packaged insight. A reader going through the piece will keep scrolling, because their brain will go “Oh, that’s interesting! And that’s interesting! And that's also interesting! Ooh, what’s next?”

As a writer, I admire what he’s done. But as a business person, nearly everything that Perell says in the piece about business is subtly wrong — enough to make me treat his essay as entertainment, not education.

Chin also talks about how self-help writing on mental models isn’t as helpful as it claims to be. He advises against reading blogs like Farnam Street—which claims on its front page that “Our Content Helps You Succeed In Work and Life”—because doing so is like trying to become an MMA fighter by only listening to people talking about MMA (similar to my post about how tweets won’t save you):

It’s obvious that you can’t get good at martial arts without practice. Without practice, and without ascending the skill tree that these MMA champions inhabit, you are unlikely to understand the insights that they have to offer. And worse, if you are listening to non-practitioners parroting what they’ve heard from the fighters themselves, you are adding a layer of indirection over something that is already difficult to communicate.

As it is for MMA fighters, so it is for business, software engineering, investing, decision making, and life.

I don’t have a strong opinion about Chin’s particular examples, but I do agree that misleading insights abound on the internet, dressed up in pretty metaphors and evocative imagery.

fakeness #3: spinning in circles, chewing on yourself

We can spend a lot of time thinking over things, or talking over things, without making any real “progress”, like an animal chewing on itself:

Likewise, you can spend your entire hourlong therapy session effectively “making stuff up”:

fakeness #4: conceptual hall of mirrors

A related sense in which words can trick us is that we can become ensnared in a worldview that seems so logical that it’s effectively impossible to be argued out of. People in my corner of twitter have noted how some fans of Karl Popper/David Deutsch are ostensibly anti-dogma while somehow coming off to everyone else as intensely dogmatic.

These kinds of conceptual traps—webs of belief that are so deeply ingrained that they’ve become transparent to you—can lead not just to intellectual errors but to personal misery. Sicong wrote that his spiritual awakening hinged on recognizing beliefs about himself as beliefs, rather than as fixed reality:

I had a spiritual awakening in April of 2020. I had been living life trapped in a world of concepts, abstractions I had taken for granted as solid, real, unquestionable features of the world. My awakening was simply to see this clearly.

words as the enemy

I had a similar experience to Sicong. I’ve had a running monologue in my head since I was a kid, and it wasn’t until I first learned to meditate that I questioned what the hell this monologue actually is. By virtue of meditation practice and a few books, I discovered that I was an unwitting believer in the homunculus fallacy: the idea that inside my head there is a “thinker” who is generating my thoughts, which I identify as the essence of what I am.

Again, I confused the map with the territory: “map” here being my image of myself, and “territory” being what I actually am. Ken Wilbur describes this (emphasis mine):

Thus man comes to nurse the secret desire that his self should be permanent, static, unchanging, imperturbable, everlasting. But this is just what symbols, concepts, and ideas are like. They are static, unmoving, unchanging, and fixed. The word “tree,” for example, remains the same word even though every real tree changes, grows, transforms, and dies. Seeking this static immortality, man therefore begins to center his identity around an idea of himself—and this is the mental abstraction called the “ego." Man will not live with his body, for that is corruptible, and thus he lives only as his ego, a picture of himself to himself, and a picture that leaves out any true reference to death.

Many things about my experience of the world changed after I discovered this, and I felt like I had been duped my whole life. I began to view thoughts and language as the enemy. The occasional glimpses of wordless experience I had in meditation felt so blissful and liberating, and I wanted to be in that state all the time.

words are necessary tho lol

Unfortunately it is neither feasible nor desirable to abandon concepts altogether, at least not in the modern world. Sure, we could all get away with less chatter—both in our heads and in dialogue with others—but we can’t get away with zero chatter. Imagine trying to navigate the complexity of our social and technological world while never having learned language.

Also: all of the preceding examples of the trickery of language were described using yet more language. Words can point the way out of words1, as in some of the tweets above, and also in Zen koans.

But I want to go further than this. It’s not just that words are necessary to exist in society, or that words can point the way out of words, but also that

words are fundamental to our humanity

Sal Reyes has developed a theory of consciousness which puts language (and thought) at the center of what makes humans human, by giving us introspective access to our own “cognitive code” (emphasis mine):

Cognition in language-less mammals could produce action & emotion, but the cognitive code that generated those results remained silent. With the introduction of language & internal dialogue [in humans], that cognitive code (literally) found a voice. Hearing & experiencing within our minds the code that shapes our actions and behavior has had a transformative impact on humans, sent us on a journey like no other. Humans think to themselves about their world & its challenges using language. The experiences of all those emotions, actions, interactions, environments, objects & predictions are expressed (and intricately recorded & associated) using a sensorially-experienced, highly-complex, word-based neural code. And humans know that they are thinking about things—we are aware of ourselves & our thoughts. We’re telling ourselves the story of our lives.

Reyes points to the example of Hellen Keller to speculate about what consciousness might be like prior to language and self-awareness. Keller describes how before language, she was somehow “conscious and yet unconscious” at the same time:

“Before my teacher came to me, I did not know that I am. I lived in a world that was no world. I cannot hope to describe adequately that unconscious, yet conscious time of nothingness. I did not know that I knew aught or that I lived or acted or desired. ... Since I had no power of thought, I did not compare one mental state with another. … When I learned the meaning of ‘I’ and ‘me’ and found that I was something, I began to think. Then consciousness first existed for me.” (“The project Gutenberg eBook of the world I live in, by Helen Keller,” n.d.)

Language and thought are not purely instruments of obfuscation. They give us the ability to see ourselves in the world, and to see more of the world than our ancestors could have imagined.

who is responsible?

Who is to blame for all the trickery of language: language itself, the human who produced the deceitful words, or the human who fell for them?

The tool isn’t entirely to blame, and neither is the person who misuses it. Our minds and our words have become inextricably enmeshed with each other; our words shape us and we shape them back. We can’t entirely blame ourselves for the muddying influence of language, but we also have to take some responsibility for our relationship to it.

innocence versus knowledge, purity versus progress

The desire to escape all concepts is motivated by an intuition that pre-conceptual existence is more “pure.” There is indeed some purity and joy to complete inner silence, to the absence of thought. If you’re incapable of speaking, you’re incapable of lying. This is one reason why the company of animals brings us such relief. In The Language of Emotions, Karla McLaren talks about how as a child she was ostracized for being too honest, but found refuge in her relationship with animals:

I did try to fit in with the gang of kids in my neighborhood, but I wasn’t very skilled at dealing with people. I was too honest and too strange. I always talked about things no one wanted to discuss (like why their parents pretended not to hate each other, or why they lied to our teacher about their homework, or why they wouldn’t admit they were crushed when someone insulted them), I had serious control issues, and I had a hair-trigger temper. I ended up spending much of my early childhood with animals because they were easier to be with. I didn’t have to hide my empathic skills—I didn’t have to pretend not to see or understand my furry friends. Domesticated animals love to be seen and understood, and they love to be in close relationships with people. Most important, animals don’t lie about their feelings, so they didn’t require me to lie about my own.

On the other side of this innocence, though, is all the magical powers that language and thought have given us: art, movies, supersonic trains, physics, microprocessors, and FaceTiming your grandparents. Among others.

reclaiming naturalness

Micheal Ashcroft points out that this innocence—this effortless honesty—is not out of reach for humans just because we are self-conscious. He describes five “stages of self-consciousness” that we pass through as we mature. First we learn to speak and we become aware of ourselves, and we develop a capacity to “lie”—to be inauthentic, or unnatural. But then we can become aware of this unnaturalness, and with enough practice we can return to that childlike state of naturalness—except now we have consciously chosen to enter that state. From his post:

Stage 1: Unconscious naturalness. The spontaneous child who can only be as she naturally is, but lacks the awareness of her own state.

Stage 2: Conscious unnaturalness. The self-conscious teenager who tries on many different masks in an attempt to fit in. No longer spontaneous, but increasingly ‘held’.

Stage 3: Unconscious unnaturalness. The adult who has long forgotten that she ever put masks on. To try to be herself is only to put on another mask.

Stage 4: Conscious unnaturalness, revisited. The adult who starts to see the masks once again, but doesn’t know how to take them off. She knows she is not herself, but the final move remains inaccessible.

Stage 5: Conscious naturalness. The child’s spontaneity has been rediscovered and is able to express itself through the conscious direction of the adult. The adult is herself once again, but fully aware.

the problem is not language itself

Is it possible to think (and to speak) without being completely captured by our thoughts? Shinzen Young reminds us that thought itself is not the enemy of wisdom; it is our fixation with thought that troubles us (link to the recording):

A lot of people consider thought to be the enemy of meditation. It's like, meditation means “getting rid of thought”, or somehow turning off your mind, making the mind blank. That is possibly an aspect of meditation, but that's not really a deep understanding of the nature of thought. Thought is just one of the six senses. It's every bit a part of nature as hearing or seeing. The only thing that is different about thought is that there’s an extraordinary amount of unconsciousness and fixation associated with the thinking process.

As soon as any little thought comes up, it's got you: it's you, and it has to be played out. And in being played out it kicks up a whole bunch of other thoughts, each one of which is you, and it too has to be considered, it has to be played out, because it's a thought, and I am my thoughts. There's an enormous amount of fixation on every thought that comes up. There's a drivenness: the apparent cure for a thought is more thought.

It's not thought itself that gets in the way, it's the drivenness and fixation around thought. The whole purpose of meditation is to diminish the drivenness and fixation; when you are finally able to think without drivenness and fixation, then your ordinary thoughts turn into transcendental wisdom. That's the only difference between insight and monkeymind. When thought is driven and fixated, we call it ordinary thinking. When some of that drivenness and fixation is eliminated, thought starts to flow like a river. There's a spontaneous, effortless, “just happening” quality to it. And those kinds of thoughts contain deep spiritual understandings.

Much like we didn’t choose to be born, we did not choose to speak. We did not choose to become aware of ourselves. But now that we’re here, we can use our awareness for our betterment; we can use language to see the world more clearly. It’s not easy, but we can learn to appreciate the magic of words, while maintaining the choice to step out of them if the spells they’re casting are not useful to us.

I got this line from the subtitle of QC’s substack.

So good, Kasra. And so on board for the anti-self help stuff you’ve been doing. Needs to be said.

Since I read de Mello’s Awareness I’ve thought a lot about the separation of words and reality. How words are not reality themselves but imperfect inventions used to describe reality. And in this how words can block us from coming into contact with reality itself.

Awesome work :)

"The power of words is assumed to be only in themselves, namely there where it is not." - Bourdieu