Reading and writing in the age of language models

why care about reading or writing when the computer can do it for you?

Socrates would be delighted about the rise of large language models (LLMs). He was the one who was opposed to books because the best way to learn something, in his view, was to have direct communication with the teacher. We have that now: we can learn anything by means of a back and forth conversation with a dynamic and intelligent model, rather than a static piece of text. This completely changes the game for infovores: you now have an advanced tutor on almost any subject you can think of,1 and this tutor is available at any hour of the day and will never get tired of answering your questions.

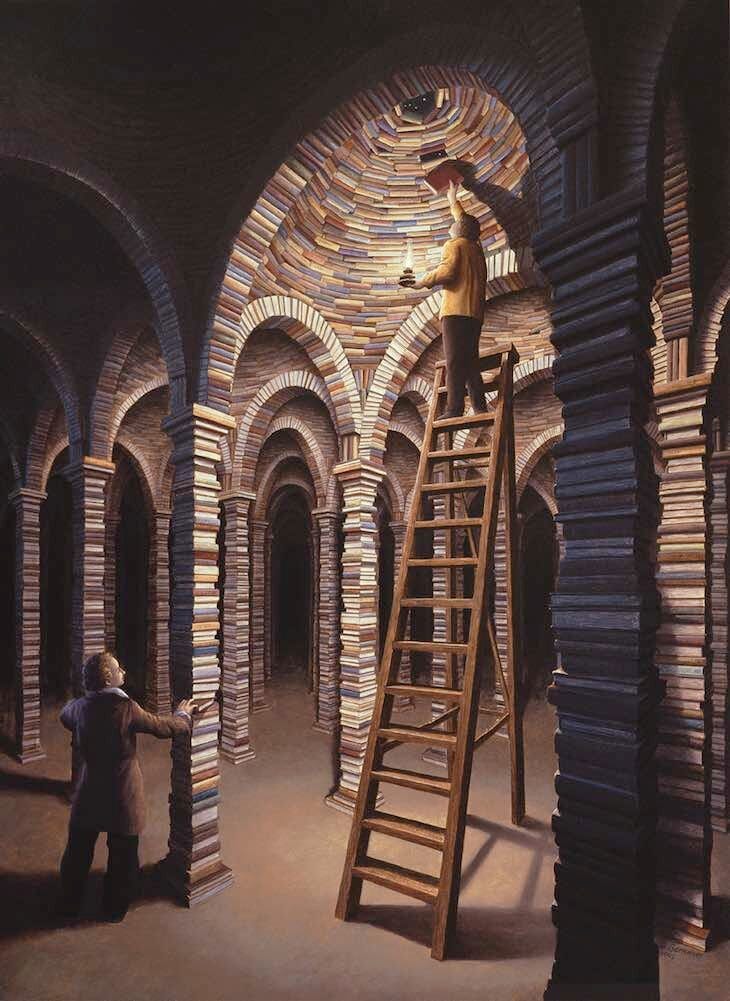

If the quest for knowledge was like fishing, then books are the equivalent of giant nets: you get a lot of good stuff with them, but they capture too much. It’s very time-consuming to scrounge through your catch to find the specific piece of knowledge you’re looking for. Language models are a fishing rod with hyperoptimized genetically-engineered bait, precisely shaped for the exact kind of fish you want.

The question that’s been on my mind since ChatGPT came out is the role that reading and writing should play in our lives, now that language models are getting better at doing both. If you can answer any question you have with a chatbot, why read books at all? Why care about how well you write when you can just have the model do the writing for you?

The problem with language models is that while they are very good at giving you the information you want, they don’t tell you what to look for in the first place. You have to figure that out yourself, and you have to learn how to be good at asking for it. This is the metaskill that has become crucial over the last few decades, when our access to information has increased and our psychology hasn’t fundamentally changed. More options—i.e., more power—means more mental clarity is needed to figure out what to do with that power. This is both a strategic problem—what information is most useful for you to know given the problems you want to solve—and an emotional one—what problems do you actually want to solve? If you want to get better at this, reading a lot (and reading widely) and writing a lot (intentionally reflecting and fleshing out your values) go a long way.

Not only that, but given that you can only communicate with language models in words, you’re fundamentally limited in what you can get from them based on how well you can articulate your ideas and questions. This limitation becomes apparent if you try asking Dall-E for something like, “an abstract painting depicting friendship”, and the result looks nothing like what you were imagining, because “painting depicting friendship” could mean too many different things. The same thing happens with writing: I tried getting ChatGPT to write about an experience I had, and I was struggling to get it to write the piece “well”, because I wasn’t entirely clear on what “well-written” even meant to me, and it didn’t help to just use words like “better” or “more eloquent.” Your usage of these models is also limited by your taste—your ability to know when to say “make this better” and when to say “this is good enough.”

Ultimately our ability to make good use of our intelligent robot friends is predicated on our ability to think, and we don’t have a good answer yet for how much thinking can be decoupled from reading/writing/speaking. They are certainly not the exact same capacity—e.g. there are some great thinkers who are mediocre writers, and some great writers who are mediocre thinkers. But I don’t think our faculties for language and thought are entirely separable either, such that we could offload all of the former to chatbots.

Who knows, maybe our technology will eventually be good enough that we can bypass words altogether and communicate with computers directly with our thoughts. Until that happens, assuming it’s even possible,2 we should continue to read and write, continue to develop our own mastery of ideas and language, while doing so in collaboration with the AI, because it is only as useful as our ability to steer it and understand what it’s trying to tell us. Our brain is a language model in itself, in need of its own training and fine-tuning.

Appendix

Examples of ways I’ve been using ChatGPT while reading, writing, and coding:

Restating a sentence from a neuroscience paper in simple words

What is alpha connectivity and how do brainwaves enable connectivity?

Is the universe made of particles or fields, and what is a quantum field?

Granted there are domains where chatbots are not very good, and they tend to hallucinate, but they do seem to be getting better very quickly.

‘maybe our technology will eventually be good enough that we can bypass words altogether and communicate with computers directly with our thoughts. Until...’

I sincerely hope this never eventuates.

In part, you are correct. It goes beyond knowing the question to ask though. If the questioner has no prior knowledge of a particular subject, or any for that matter, how do they know the machine, which is simply a predictive tool, knows the answer? How do they know when it's hallucinating? And these LLMs are rather good at that. If one does not know how to question or how to debate, then one isn't learning, they are simply absorbing. There's a difference. We should not trust that with which we cannot debate.