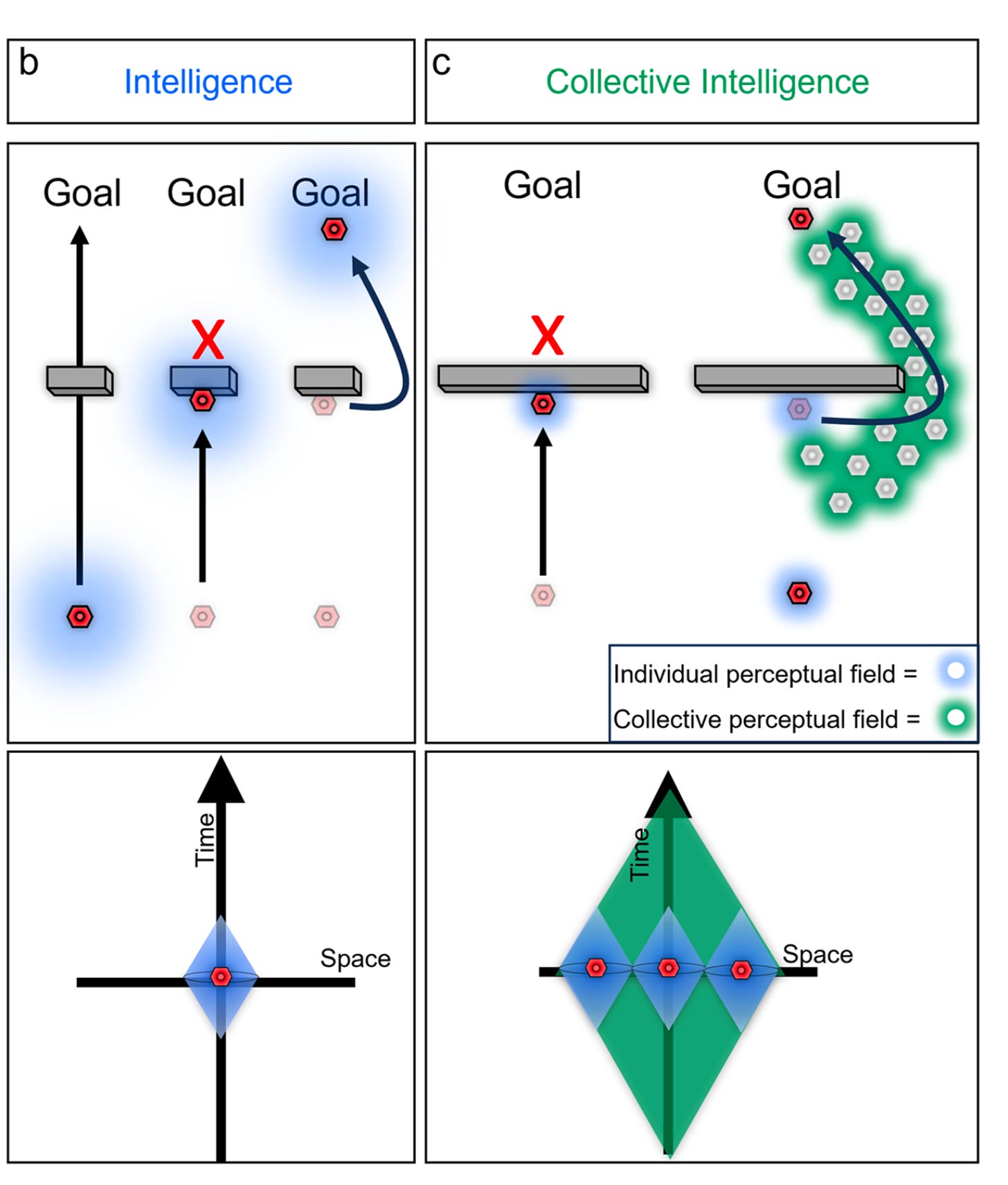

Collective Intelligence expands the perceptual field of a group of cells beyond the capacity of any individual, expanding their problem solving ability. As the size of a collective increases its perceptual field increases, improving its ability to find variant paths towards the same goal.1

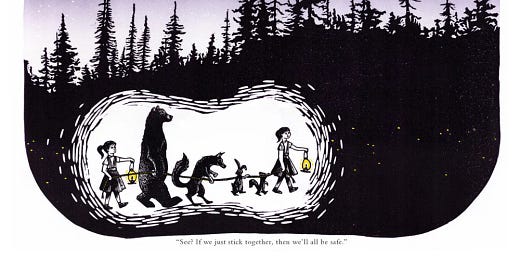

Ryan was driving. Our Airbnb host left us a note wishing us a good stay and to text her if we need anything. Tiff and Anna scoured weather maps to figure out where we can find the least cloud coverage with a decent chance of parking. There was a government text alert: Do not stop at the side of the road to view the eclipse, so that emergency vehicles can get by. Someone made a 22-minute science video detailing everything we need to know to prepare. Small-business owners manufactured glasses for staring at the sun, and other people uploaded videos reviewing those glasses, to let other people know whether they’re comfortable or fashionable or up to standard. Friends checked in to make sure I procured glasses, that I won’t look at the sun directly. Someone paved the roads for us to drive on, someone made a website with interactive maps of all the towns in the band of totality, someone made an app alerting us to the exact moment of contact. We are all sheltering each other with blankets of care.

Self-reliance and self-optimization are the mottos of the day: if you want safety you better find it in yourself. But you can never be truly self-sufficient—the very nature of your “self” is constantly changing, constantly in flux with your environment. You mime the desires of your peers; you live at the mercy of vast networks of utilities and power lines that keep your lights on and your water clean; you depend on the microorganisms in your gut and on your skin. You depend on the grasslands that feed the cattle that feed you.

My lease is ending again soon, another round of condensing my life into a set of cardboard boxes for easy transport in a truck, an experience that always gives me existential unease. All I remember from the last time it happened is the way my friend’s presence steadied me, as I unpacked my belongings into the new shoebox that New Yorkers call a bedroom. He stood there between the rows of unopened boxes, the little standing space there was, as I worriedly put books onto my shelf and taped up my string lights. You think it’ll be ok if I only have this much space? If I have to sleep with earplugs every night? If this much silt is falling off the walls? Gently, smilingly: Yes, yes, and yes. I wrote an entry in my journal that night with the title: human company as a prophylactic for neuroticism.

At some point in evolutionary history, all life was unicellular, the only notion of “selfhood” being that of a cytoplasm contained inside a cell membrane. Over time, these single-celled beings began cooperating, and eventually they became one. Their problem-solving capacity grew with their size; with each layer of complexity they came closer to what we now call “intelligence.” A single cell cannot see past a wide barrier; a collection of cells can coordinate with each other to form a path that gets around it. A single human cannot see far enough or jump high enough to fly into space; a collection of them can build prosthetic eyes and jet-propelled legs to break past the blue dome of our atmosphere. The collective has a “field of vision,” a “space of possible actions,” which contains and supersedes that of each individual.

There’s a lot of talk today of emotional safety. We view other people as dangerous, as threats to our sense of inner calm. The very notion of “emotional safety” betrays how safe our lives have become, how much physical protection we provide for each other. We forget how sheltered we are until the moment there’s a war or a terrorist attack or random act of violence at close quarters. It’s understandable to view other humans as threatening: people are at the root of many of the biggest dangers that we face. But the only thing that protects us from that danger is yet more people: kinder, more thoughtful, more caring people.

It’s true that complexity growth and social progress don’t happen in a perfectly linear fashion. Progress occurs through cycles of advancement and collapse, and there are frequent reverses in the trend. It is a constant battle between order and chaos, with advances in technology happening simultaneously as events of great destruction. But that’s exactly how adaptive systems become more resilient. Social systems are constantly being tested by nature’s hostility, and this exposes weaknesses in the organization of their structure, and then solutions must be invented.2

Some observations: every day we climb up to heights from which we would die if we fell, we come within arm’s length of vehicles ten times our mass moving faster than the speediest predators, we step into slender stone structures which would crush us if the balance of mechanical and gravitational forces wasn’t calculated just right, we walk and sit within earshot of electrical wires powerful enough to fry our bodies. Why then do we go about our day so unbothered, so concerned instead with less material threats to our wellbeing? Because of the carefulness of other people.

It’s four thousand years ago, and an earthquake in central China sweeps across a village, in the middle of which there is a woman attempting to shield a young child; they don’t survive, but their entwined skeletons are uncovered thousands of years later, her act of care permanently etched into the earth’s crust. It’s 1986, and physicists John Barrow and Frank Tipler put forth the bold and controversial thesis that “intelligent information-processing must come into existence in the Universe, and once it comes into existence, it will never die out.”3 It’s the 1980’s, and a former navy pilot named Charles Plumb, who had to eject from his plane during combat because it was shot down, runs into the man who packed his parachute a decade earlier, a man he thanks for his survival. It’s the turn of the century, and you are coming into existence as a clump of tiny undifferentiated cells, which alone would die off and amount to discarded flesh, but which together orchestrate a complex bioelectrical dance that eventually forms you.

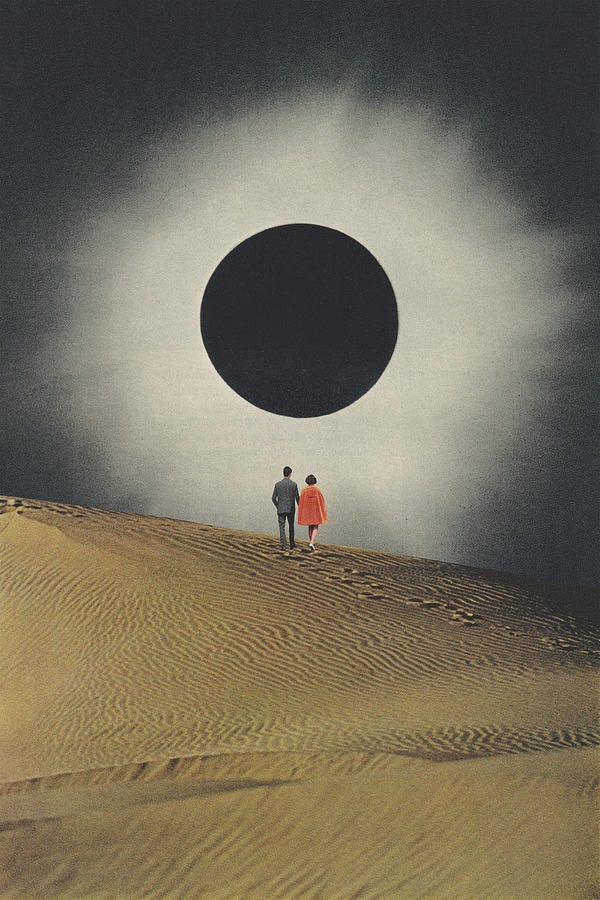

Upon witnessing a total eclipse, the common refrain is that it is humbling. I too felt that humility: the gaping hole in the sky was larger, more awesome, more awful than anything I’d ever seen. But in the moments before and after, I could only see the innumerable ways we depend on and strengthen one another. An eclipse occurs at the same location once every 375 years, on average. We know nothing else about what will be going on here then, but we know this. The moon will once again swallow up the sun, casting a shadow that dashes across earth’s surface at 1800 miles per hour, unconcerned with the presence or absence of astonished onlookers. These are celestial events beyond our control, beyond our perceptual horizon. What chance do we have of influencing this world? What do we have in the face of such enormous cosmic forces? We have each other.

Thanks to Varun for feedback on this and many other drafts.

From McMillen & Levin 2024.

Beautiful. We are all walking alongside each other.